For the Birds

Some cat owners probably awoke this morning to a carcass on their doorstep: a bird, a mouse or maybe a mole. These “gifts” are tokens of their feline’s late-night prowling and a glimpse of the ecological havoc wreaked by the domestic cat.

Cats in the United States kill an estimated 1.4 billion to 3.7 billion birds each year—numbers much higher than previously thought—according to a 2013 Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service peer-reviewed analysis of previous studies. The scientists also found that cats kill 6.9 billion to 20.7 billion mammals a year.

While feral and stray cats are the biggest culprits, about half of the 80 million or so companion cats in this country roam freely at least part of the time, catching an estimated 1.9 billion wild animals a year. “Cat predation is more than a minor threat to wild animals,” says Smithsonian biologist Peter Marra. “Our study demonstrates that cats outstrip assessments of annual bird deaths from pesticide poisonings and from collisions with windows and communications towers.”

While feral and stray cats are the biggest culprits, about half of the 80 million or so companion cats in this country roam freely at least part of the time, catching an estimated 1.9 billion wild animals a year. “Cat predation is more than a minor threat to wild animals,” says Smithsonian biologist Peter Marra. “Our study demonstrates that cats outstrip assessments of annual bird deaths from pesticide poisonings and from collisions with windows and communications towers.”

A descendant of the wild cats of Africa, the domestic cat first came to North America in large numbers in the 1800s. Because native species didn’t evolve alongside it, their natural instinct to avoid it is weak. Further, cats compete with owls, hawks and other important wild native predators that aren’t subsidized by people and need their prey to survive.

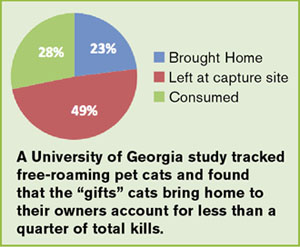

People often believe that cats won’t hunt if they’ve been well fed, but hunting is an instinct separate from the urge to eat. University of Georgia researchers found this out when they fitted 60 free-roaming, local pet cats with camera-collars and collected about 2,000 hours of footage. This cat’s-eye view of nightly activities found that 44 percent of “kitty cam” house cats hunted wildlife. When these cats killed, they brought only about a quarter of their prey home as gifts, snacked on some and abandoned the majority. says Kerrie Anne Loyd, the study’s lead.

“It’s true that bird deaths occur from many other hazards and we need to continue to improve wind turbines and communication towers, for example, to help migrating birds,” says Marra. “But we can’t pretend that the cats we let roam outside don’t take a tremendous toll. The bottom line is you can do something every day to help native wildlife—and it has the added benefit of helping your pets live longer.” –matthew hardcastle

Did You Know?

• Cats likely kill more wildlife in spring and early summer than any other time of year because fledging birds and other newborns have not developed any physical defenses or awareness to the dangers of their world. Typical cat prey includes robins, cardinals, bluebirds and warblers.

• Keeping cats entertained indoors is safe for your cat, too. The kitty cams project caught cats frequently engaging in risky behavior like exploring dangerous spaces including storm drains and crawl spaces, where they could become trapped.

• If your cat is too old to retrain for indoor living, attach a bell or anti-pouncing “cat bib” to a breakaway cat collar to reduce hunt success.