Mollie Beattie, the first female director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service once said, “What a country chooses to save is what a country chooses to say about itself.” That rings true even today, and applies to not just the country as a whole but also to individual states as the custodians of our natural resources. In a biodiversity extinction crisis, the needs are many, resources are limited and tough decisions have to be made on setting priorities. So what are we prioritizing in wildlife conservation efforts?

The simplest way to find that out is to follow the money and the spending of state fish and wildlife agencies. But when you do that, it paints a bleak picture. Take Oregon, for example. A public agency like Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) is expected to be largely funded by government dollars collected from the public, such as through taxes and other funds. In reality, that is not the case. The graph below makes it starkly apparent that ODFW is minimally supported by state funds and most of its funding comes from hunting and fishing related sources.

In their 2021-2023 biennium budget, general funds and lottery funds combined account for only 10 percent of their funding, while hunting and fishing license sales along with excise tax on sale of guns and ammunition (also known as Pittman Robertson funds) accounted for 48 percent. Additionally, a significant portion of these funding sources comes with restrictions and sideboards on what they can be spent on. For instance, Pittman Robertson funds cannot be spent on research or management of amphibians and reptiles because such species are rarely hunted; federal contracts often come for specific programs and projects and cannot be used elsewhere.

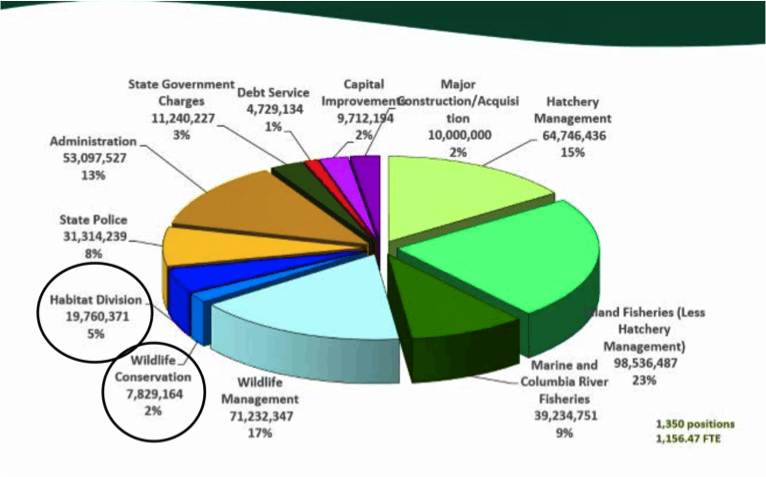

Does it surprise anyone then, that the agency prioritizes game species management even though 88 percent of Oregon’s species are not hunted or fished? The graph below of ODFW’s 2021-2023 spending shows how little goes exclusively to wildlife and habitat conservation. The agency is protecting its main income source, logically so. If consumption and use of wildlife brings the most revenue, then it is inevitable that wildlife will be treated as a commodity that should be protected for consumption alone. The demand creates the supply. This is true for many states’ fish and wildlife management agencies in the U.S.

The Public Trust Doctrine establishes the government as a trustee that holds and manages fish and wildlife for the benefit of the resources and the public. Sadly, we have chosen not to invest in this critical resource. Most members of the public are unaware that a public agency protecting a public resource is not funded by public dollars. We need states to take ownership and be accountable for vulnerable wildlife and their habitats by investing more dollars in agencies responsible for protecting them. If general fund dollars are falling short for this purpose, states have the option to explore other consistent streams of funding that can be specifically dedicated for funding wildlife conservation and habitat protection such as surcharges on goods, travel or other expenses that people make to enjoy wildlife.

Wildlife and wild places are important resources that need to be protected for the resiliency of the planet and its people against climate change impacts and other anthropogenic pressures. It is an important issue to invest in, for the sake of this generation and future generations to whom we owe these resources.