As we face unprecedented extinction rates, the nation’s remaining wild places are more important than ever—yet their continued existence is under increasing threat

Increasingly, we live in an environment fundamentally transformed by humans. More than 90% of our lives are spent in human-made spaces – buildings, cars and parking lots, supermarkets and subdivisions – that we carefully construct to meet our own needs. Even the manicured turfgrass of the White House Rose Garden was paved over recently after being deemed too rugged. From this hedged-in vantage point, it is easy to lose sight of the vast wildness encompassed in our national forests and the multitude of wildlife these lands support.

Our national forests are managed on a spectrum; untouched wilderness on one end and timber sale areas and oil and gas fields on the other. In the middle is a land designation called Inventoried Roadless Areas, where timber harvesting and roadbuilding are restricted for the benefit of stewardship-management and backcountry recreation. In August 2025, the Forest Service proposed eliminating these protections, opening vast tracts of prime habitat to commercial logging.

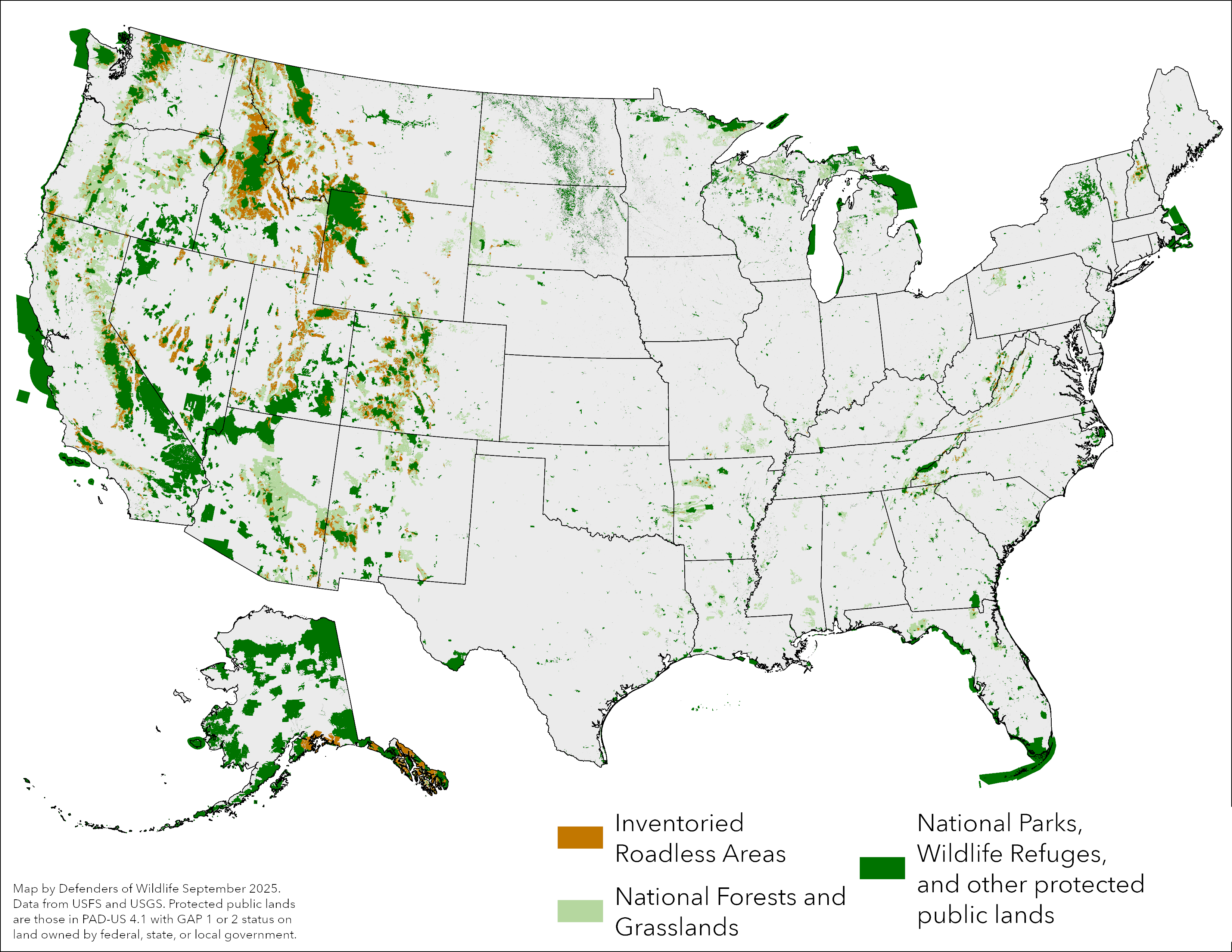

These backcountry areas are managed according to a regulation known as the Roadless Area Conservation Rule. Almost one-third of our national forest lands – from Florida to Alaska – benefit from Roadless Rule protections, and these areas contain some of the wildest places left in the country.

More than 80% of the forests on Earth have been degraded by activities such as industrial logging and infrastructure. Those that remain, such as in protected roadless areas, have exceptional value for biodiversity conservation by providing quality habitat for a multitude of wildlife especially those that are sensitive to disturbance or need big, wide-open spaces to roam and migrate.

Wildlife - Big and Small - Need Roadless Forests

Roadless forests support many rare and secretive creatures that you may otherwise never be lucky enough to see in the wild. But roadless areas are also closer than you think, making positive impacts in ways we may not realize.

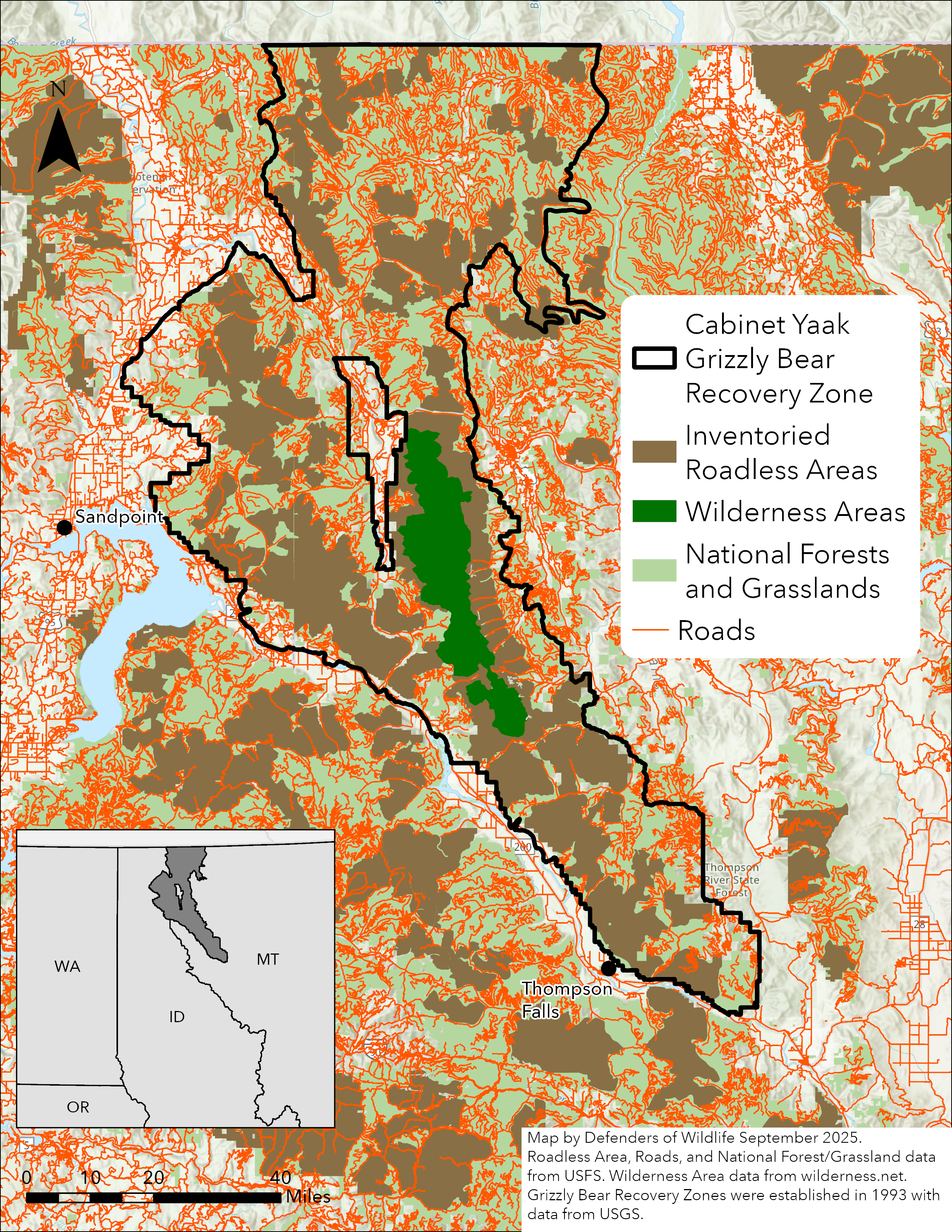

About 40% of Forest Service roadless areas are directly adjacent to protected areas, which increases their effective size and connectivity. Large animals such as the grizzly bear (listed under the Endangered Species Act) depend on these large tracts of secure habitat away from roads to move safely across their range.

For example, within the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem, which supports a small population of about 67 grizzly bears spread across northwest Montana and northeast Idaho. Almost 40% of Cabinet-Yaak grizzly bears’ habitat is in roadless areas, and the loss of conservation protections would be devastating for a population that already faces connectivity challenges and has not yet reached recovery goals.

Roadless areas benefit large, wide-ranging wildlife as well as smaller ones that experience roads as a formidable expanse, isolating them from otherwise available habitat. The relictual slender salamander, proposed for listing as federally endangered, is one such short-legged creature that may move less than 60 feet in its lifetime.

This tiny amphibian occurs on a single mountaintop in California, where half its habitat is protected by roadless regulations. Outside of those protected lands, habitat degradation from road construction and maintenance has already extirpated the species from much of its former range. The rescission of the Roadless Rule could obliterate its little remaining habitat, risking its extinction.

Roadless areas also contain rare and diverse plant communities, in part because they lack roads to introduce invasives. Among the largest remaining roadless landscapes in Oregon, the Kalmiopsis ecosystem is considered a botanical treasure. The region is named after the Kalmiopsis leachiana, a rare, ancient flowering shrub. It is one of the most botanically diverse areas in North America, supporting several other rare plants like the carnivorous California pitcher plant.

In a world where undegraded lands are scarce, our remaining wild forests have more value standing tall than stumped and sold.