The states of Washington and Alaska may be roughly 3,000 miles apart, but they have two types of bears in common: brown and American black bears. Another commonality is Defenders of Wildlife has teams working on the ground in both states to shift how we manage human-bear conflicts by aiming to prevent them before they occur.

There are a lot of similarities and some key differences between the bears and the work. When we come together, we open the door to some novel solutions for bears and people across both states.

Before discussing how Defenders works to prevent human-bear conflicts in different environments, though, let’s first understand the animals and their diets:

Meet the Brown Bears (Ursus arctos)

While brown bears in Alaska and Washington are biologically the same, their homes have shaped their differences.

Washington brown bears are the same subspecies we know so well from Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks: Ursus arctos horribilis or grizzly bears. Currently, only 50 to 70 grizzly bears are found in the far northeastern corner of Washington in the Selkirk mountains, which extend beyond Washington's borders into the Idaho Panhandle and British Columbia. Historically, they also roamed the North Cascades of Washington and British Columbia, but unregulated hunting and predator culling programs in the 1800s and 1900s wiped them out of this area.

Alaska, in contrast, has one recognized subspecies of brown bear: the Kodiak bear (ursus arctos middendorffi). Over the years, genetic research has reduced the number of subspecies thought to exist, but more research is still needed to fully understand how many subspecies of brown bear exist in North America and beyond. What is not contested, however, is Alaska’s geography significantly reduces connectivity between bear populations in some areas. Defenders in Alaska is particularly concerned about conflict-related bear mortality in populations that are geographically isolated from other bears, such as those on the Kenai Peninsula of Southcentral Alaska and in parts of Southeast Alaska.

A common misconception is Alaska’s interior bears — often called grizzly bears — are a different subspecies from the coastal bears. Rather, the differences between the two — like their varying sizes — can be attributed to their environments.

Meet the American Black Bears (Ursus americanus)

The name “black bear” is a bit of a misnomer. These bears actually come in a variety of colors, including black, chocolate and cinnamon. In certain regions of Alaska and Canada, there are also blue-back and white colorations, commonly known as glacier and Spirit/Kermode bears, respectively. Similar to brown bear subspecies, it is debated whether several of these color morphs are indicative of a separate subspecies, or just a cool demonstration of gene mutation and how animals can adapt to their surroundings.

Take the Glacier bears for example. Their coloration is unique to the northern part of Southeast Alaska and northwestern British Columbia. It is believed to be an adaptation that allows them to better blend in with a glacial environment. Currently, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game considers Glacier bears a subspecies of black bear but also recognizes further research on these bears is still needed.

Black bears are widespread in both Alaska and Washington. Black and brown bears in Alaska often occupy the same areas, though in Southeast Alaska, some islands are home to both while others are predominantly inhabited by one. In Washington, black bears can be found in pretty much any forested area and are thriving — with a population of over 22,000 bears — across the state.

Beary Different Diets

Although bears are classified as carnivores, they are actually omnivorous and eat plants (grasses and sedges), insects, berries and meat. Surprisingly, Washington grizzly and black bears diets are actually comprised predominantly of non-meat food options such as berries and vegetation. For instance, only 12% of a Selkirk grizzly bear’s diet is from animal matter, with most of that likely being opportunistic of a carcass or newborn elk or deer.

While Alaskan Interior black and brown bears have similar diets to Washington’s bears, the diets of coastal bears contain significantly more meat, with salmon representing more than 60% of a brown bear’s diet in coastal areas like Southeast Alaska, the Kenai Peninsula, and the Aleutian Islands.

How Defenders works in different environments

While keeping the differences in mind, Defenders employs many of the same tools to help people live in both regions with both types of bears.

Bear-resistant garbage cans, food storage lockers and bear boxes are effective at keeping brown and black bears away from garbage and food in both states. Additionally, electric fencing is also effective across states and species. Differing environments, however, may impact fence construction, primarily because soil conductivity is very important to electric fence function.

Just like you have to get out of the pool when lightning is detected nearby, wetter climates and soil — like those found in Southeast Alaska and western Washington — conduct electricity better. Dry, rocky ground is your nemesis because it’s a poor conductor and fences risk having poor voltage and, therefore, lower shock power. This can result in a fence that is essentially useless at deterring bears. In eastern Washington and parts of the Kenai Peninsula, where this soil type is common, electric fences are designed to compensate for this particular challenge.

Keeping vegetation away from fence lines is also important to prevent the fence from “grounding out” and decreasing the voltage along fence lines. In Alaska, where vegetation grows quickly because of increased sunlight in the summer, trimming vegetation away from the fence is an almost daily maintenance activity. While there are areas in Washington with thick vegetation, the east slope of the North Cascades has slower regrowth and requires less vegetation maintenance.

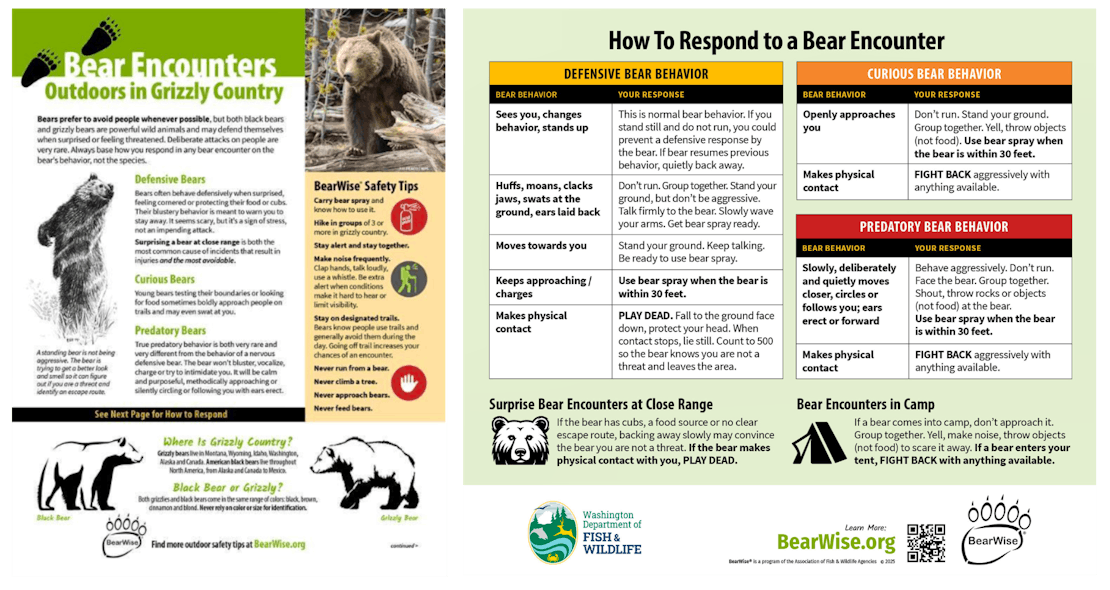

What to do if you encounter a bear

Regardless of where you are, or the type of bear, four things always stay the same when in bear country:

- Always carry bear spray

- Never intentionally approach a bear

- Never run from a bear

- Respond to the bear based on its behavior, not its species

Bear in mind these extra tips for staying safe while in bear country with Defenders PLAY SMART guide.