“My ocean.” That’s what one of my professors from college had on his license plate. That’s what he taught; that even in the middle of upstate New York, even in Kansas and Germany and Paraguay and Chad, people should care about the ocean. It’s your ocean. You have the power to keep it clean and protect its wildlife.

Maybe you are lucky enough to visit your local aquarium, go snorkeling or scuba diving near a barrier reef, or have a house by the beach. But do you think of the ocean as your ocean?

Long Beach Island is like a second home to me, and I frequently think of that stretch of barrier island as my own. It’s where I fell in love with the ocean; walking in Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, seeing osprey hunting in the ocean, watching pelicans dive for fish, swimming among cownose rays, and cheering for dolphins riding the waves. As I got older, I had marine experiences around the world, expanding my horizons, both literally and figuratively, and I began to think of the ocean as my ocean.

I spent an entire summer in Hawai`i working with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), swimming with more turtles than I could count, learning to identify more fish (with the craziest names) than I could imagine, and working to promote marine science that is having an impact on ocean conservation. I also went to Belize on another whirlwind marine adventure. I was on Glover’s Reef with a group of volunteers assisting in shark and stingray research and for a week we went out on the water every day to hand-line for bait and ultimately find and tag sharks. The volunteers came from all walks of life and we snorkeled, marveled at the diversity in the patch reefs, and were fascinated watching reef sharks hunt stingrays from the tops of reefs.

No matter where I travel, one thing remains the same— our oceans are in trouble.

Marine debris is one of the major threats to our oceans, and it ends up in places where there aren’t even any people. Take the Northwest Hawaiian Islands. The islands act like a comb in the middle of the ocean currents circulating in the Pacific, just raking and catching all of the plastic, glass, rubber, and random items that end up in the ocean. NOAA sends teams to these uninhabited places to remove all of the traces of human garbage they can find, but more always finds its way to the shore, and birds, marine mammals, turtles, and fish are injured, often to the point of death, after ingesting plastic or becoming entangled in (often derelict) fishing gear.

Entanglement in fishing gear poses the deadliest threat to the North Atlantic right whales’ survival. With fewer than 450 left in the ocean, and no known calves born this year, these whales are in an increasingly tough spot.Defenders is a long-time member of the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Team, and we are working to prevent entanglements by pressuring the National Marine Fisheries Service to implement effective and innovative solutions.

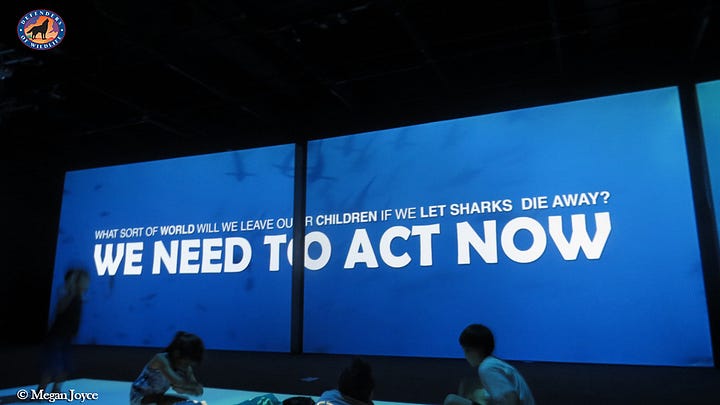

Marine debris and entanglements are only two of the problems facing marine species. Shark finning is another deadly threat to the inhabitants of the ocean. It involves catching sharks, hacking off their fins and tails — usually while they are still alive — and throwing them back in the water. Unable to swim, the sharks then bleed to death, starve or drown. Every year, 73 million sharks are killed for their fins in the gruesome practice. The popularity of shark fin soup as a delicacy has led to the mass slaughtering of many different species of sharks and stingrays. Defenders advocates all over the world for conservation measures protecting these great ocean predators. At the Conference of the Parties to the Conference of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS COP12) in Manila, Philippines, we had a major success in securing protections for migratory sharks and rays!

I do think of the ocean as my ocean. I think of the ocean as our ocean. And our ocean is in trouble. It is part of my duty, our duty, to protect it and the lives that rely on it. Just as looking to the end of the ocean is impossible, knowing where I will end up throughout my life is not predictable. What I do know is that I will fight for my ocean, your ocean, and our ocean. I will fight to protect everything the ocean represents to me, my childhood and my experiences in the great outdoors, and all of the life that lives in the sea.

You can help us turn the tide for the ocean. Even small changes, like refusing to use a plastic straw or keeping a reusable bag with you, can add up and make a difference for marine wildlife. I will be marching on Saturday, March 9th, in the inaugural March for the Ocean, alongside my fellow Defenders and ocean legends like Dr. Sylvia Earle, Philippe and Ashlan Cousteau, Carl Safina, and Danni Washington. I hope that you will join us!

The March for the Ocean is about the survival of our blue planet. But it’s also about the fact that it’s not too late to turn the tide — to restore and protect what we love. March for the Ocean — for water — for our future and say NO to offshore oil testing, leasing, drilling and spilling; YES to corporate accountability for plastic pollution; NO to plastic and other forms of ocean pollution; YES to protecting our coastal communities; and YES to a healthy ocean and clean water for all — not least of which are all of the incredible species that call the ocean home.