The First Great American Extinction Event (Approximately 13,000–11,000 years ago)

Contrary to popular belief, today’s extinction crisis is not a new or even recent development. Although the pace has indeed increased, the general trend is one as old as mankind. From the moment modern people set foot in North America, a devastating cascade of extinctions has swept across the land and hit animals big and small. In a three-part series, we will explore that history, the wildlife lost over the course of ten thousand years, and how our violent past can inform how we treat wildlife today.

For millions of years, long before humans arrived on the continent, the land teemed with giants.

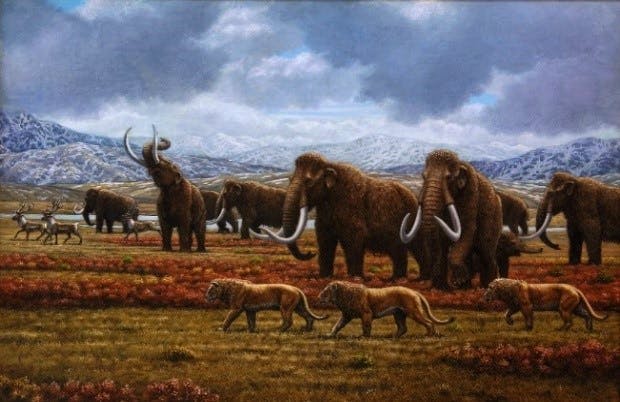

Until around 13,000 years ago — a blink of an eye, ecologically speaking — various species of mammoths and mastodons browsed upon elephant-adapted trees and shrubs that persist today. Like their African counterparts, these animals were critical to the health of North American ecosystems and, through their pruning and clipping, created niches for hundreds of other species.

They were accompanied by a suite of other giant herbivores, including ground sloths. Ranging from Alaska all the way to the tip of South America, various species of sloths once roamed much of the Western Hemisphere. In North America, the largest weighed in at around 6,000 pounds. They walked among giant bison, which stood seven feet tall at the shoulder; American camels that browsed upon the thorny plants that most of today’s animals find unpalatable; bear-sized beaver, giant armadillo, and tapirs among others.

When people first descended into North America, they encountered these herbivores, as well as a dazzling array of carnivores.

American lion, one of the largest cats to have ever lived and nearly twice the size of an African lion, hunted wild horse and bison on the plains. American cheetah chased down the ancestors of modern pronghorn — North America’s fastest land mammal extant today. Sabretooths hunted in packs and specialized in preying on young elephants. The animal made famous by Game of Thrones, the dire wolf, also stalked prey among these large cats. None, however, compared to the gargantuan short-faced bear. Standing 13 feet tall on its back legs, these beasts weighed a ton — nearly three times the size of modern grizzlies — and ate 50 pounds of meat a day (they probably specialized in stealing giant carcasses).

Never in history had modern humans encountered such an array of large predators and prey. One can only imagine the sense of awe and fear they must have inspired.

Unfortunately, those giants didn’t last long. Shortly after people arrived, the megafauna vanished.

Damning evidence indicates that, although climate change was at play, we were probably the deciding factor[1]: virtually no trees, plants, or small mammals went extinct during that time[2] — only the big, conspicuous species. Until the moment the great elephants went down, their tusks were growing larger and they were breeding, indicating they were well-fed.[3] And we now know that every continent’s megafauna — except for Africa and parts of Asia, where wildlife evolved to fear us — disappeared at nearly the exact moment humans came onto the scene.[4]

In North America, this mass vanishing was so great, 73.3% genera of large mammals went extinct shortly after people arrived. The giant mammals that once defined the American wild became fossilized memories, in fewer than a thousand years. These extinctions accelerated as people spread into South America and, eventually, even the world’s most remote islands. By the time the global migration of people came to an end, half of the planet’s genera of large mammals had vanished.

With this history in mind, it’s accurate to say that North America closely resembled an African game park for millions of years. Like the giraffes, lions, and elephants of Africa, our country’s ecosystems were run by sloths, sabretooths, and mammoths.

For those armed with this knowledge, it’s difficult to look at modern ecosystems in the same way again. Today’s wolves and bears are simply pieces of a hugely incomplete puzzle. Yet, this history is critically important because it sets a baseline for measuring ecosystem health and dynamism. It also has the potential to energize greater conservation action for the animals that survived and remain today.

In the next chapter, we’ll discuss those species and how they fared during the Second Great American Extinction Event, thousands of years later.

In the meantime, be sure to check out your local natural history museum. There you can, with a little imagination, behold the giants of our not-too-distant-past.

Full Series:

The Three Great American Extinction Events — A Brief History

The Second Great American Extinction Event (1600s to 1900s)

The Third Great American Extinction Event (Present Day)

[1] Richard A. Kerr, “Megafauna Died from Big Kill, not Big Chill,” Science 300 (May 9 2003).

[2] Paul Martin, Twilight of the Mammoths (University of California Press, 2005) 172.

[3] Peter D. Ward, The Call of Distant Mammoths (Copernicus, New York, 1997), 113.

[4] Kerr, “Megafauna Died from Big Kill, not Big Chill.”