“Just walk past the beach volleyball court and turn right at the T. rex.” These were the directions Mike and I got as soon as we arrived on Google’s campus for the Geo for Good Summit. Google’s campuses in the Silicon Valley certainly lived up to the crazy, creative, colorful descriptions I imagined when hearing about the tech giant. Rather than take time to explore the campus and admire its Jurassic landmarks, however, we were there to take a deep dive into the many mapping tools Google provides—all for free—because of how they can help conserve species. We weren’t alone, with around 350 members of the mapping, non-profit, and/or programming and development communities from all around the world in attendance too.

Mike Evans, our Senior Conservation Data Scientist, and I are part of the Center for Conservation Innovation (CCI) at Defenders of Wildlife where we work at the intersection of science, technology, and policy to find creative and practical solutions to improve wildlife conservation. One of the ways in which our team improves wildlife conservation is by attending and presenting at conferences and workshops all over the globe. In 2019 alone CCI has been represented at six different conferences as close as Washington, D.C. and as far away as Malaysia. Sharing ideas, professional connections and collaboration, and the general inspiration that comes from these experiences improves the quality and breadth of our conservation work. The Geo for Good Summit was no different. In fact, it served as a nexus for our work, covering all three aspects of science, technology, and policy through a geospatial lens – just my specialty as the GIS and Technical Computing Associate!

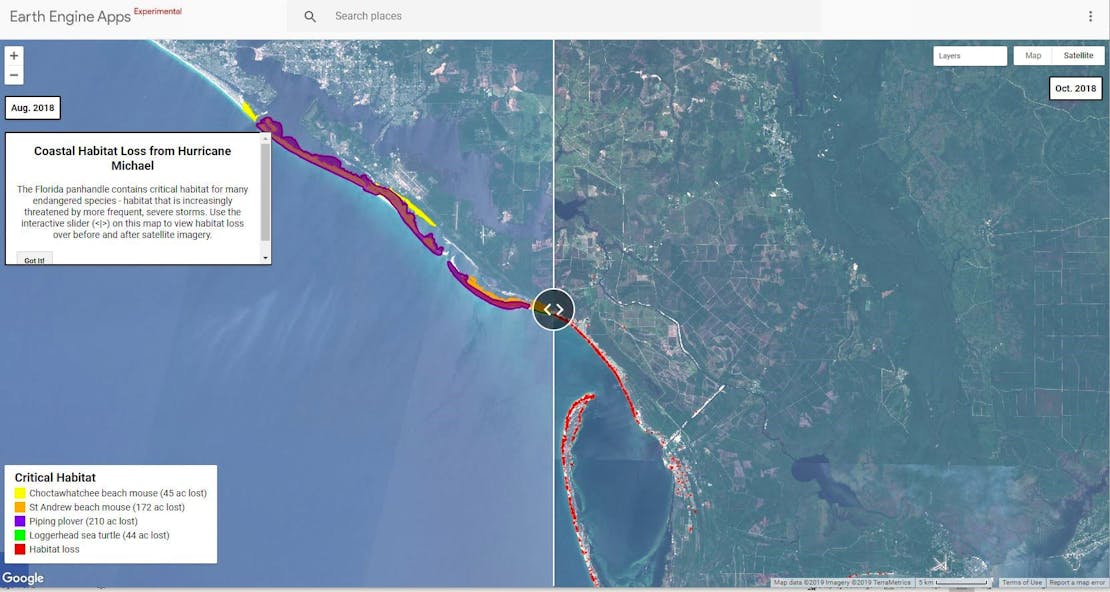

The Center for Conservation Innovation has been using Google mapping tools for a variety of projects. For example, Mike uses Google Earth Engine for finding habitat that has been developed or has otherwise changed over time by running change detection algorithms. He’s even put some of these results into handy Google Earth Engine Apps to easily view these changes in the landscape, like the one below showing the loss of habitat for threatened and endangered species after Hurricane Michael. I, on the other hand, have just begun integrating some of Google’s mapping tools in my efforts to effectively communicate our geospatial work through storytelling platforms like Voyager.

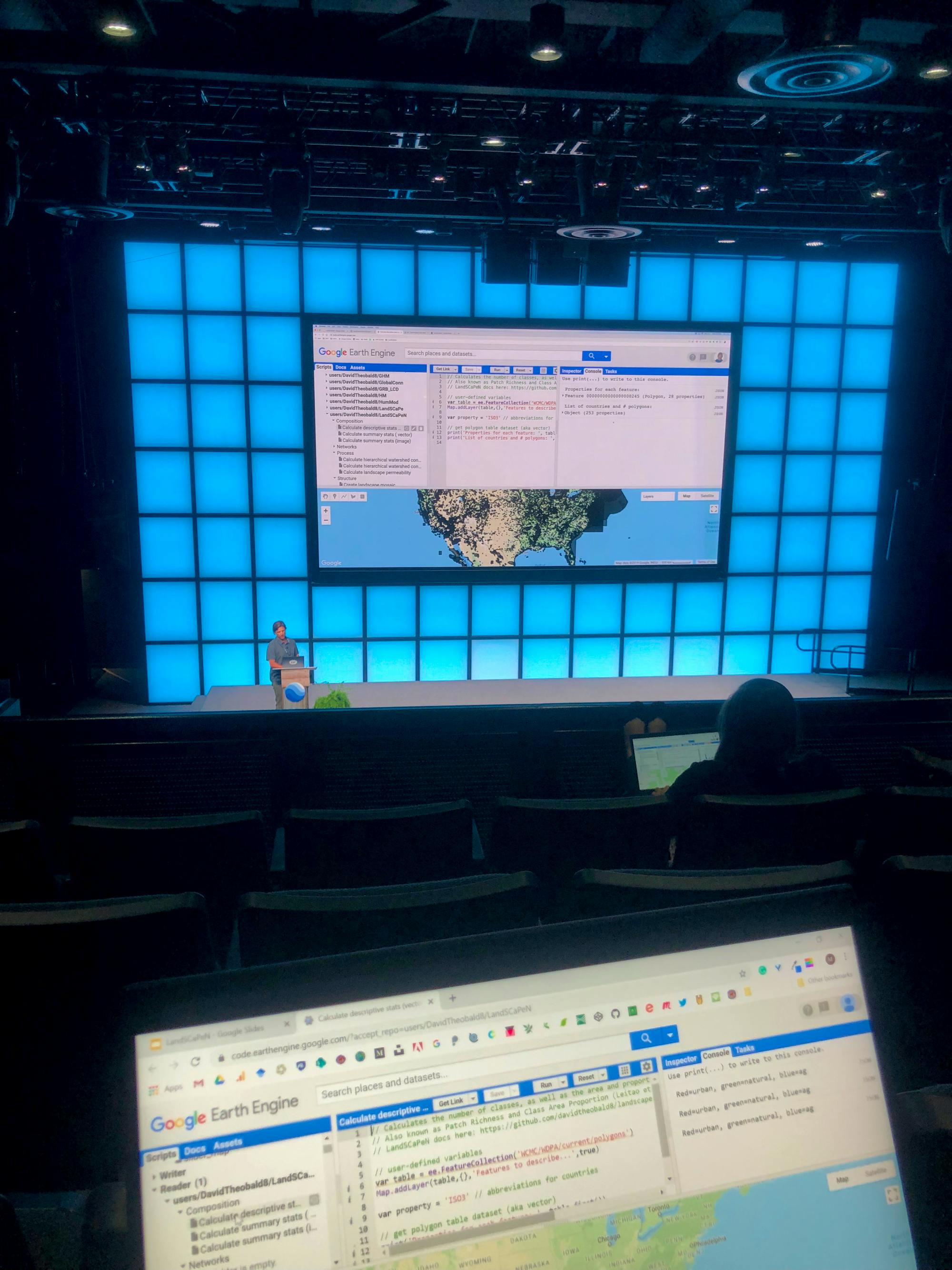

From time lapses of surface mining in Appalachia to tools like TensorFlow and BigQuery, Mike and I were able to immerse ourselves in the land of big data, machine learning, geospatial analysis, and creative approaches to maps and storytelling. Press play along the years at the bottom to view surface mining over time in the Appalachians.

We bounced from talks on how to code analyses of habitat connectivity in Google Earth Engine to demos of Google Earth Studio’s ability to create videos virtually “flying” through three dimensional imagery of cities and landscapes all over the globe. Mike even gave a talk on the applications of automated changed detection to monitor oil and gas development in the Lesser Prairie Chicken’s range, and sand mining operations in the dunes sagebrush lizard’s range.

We were able to both share and gain skills to not only dig deeper into our spatial science, but also learn how to use these different tools to communicate our work with audiences outside of the science community – one of the major but often overlooked components of our work as scientists.

In addition to how much we learned at Geo for Good, one of the best parts of attending conferences like this is being surrounded by people who are on the cutting edge of harnessing the seemingly unlimited potential of this technology for the things that matter most to them. For some attendees, harnessing this potential means developing the world’s first satellite-based alert system for threats to mangroves at only 16 years old and for others this means building a dataset to visualize conservation data globally. Here at Defenders, we are using this technology to track the loss of habitat for threatened and endangered species such as the Choctawhatchee beach mouse, the St. Andrew beach mouse, the piping plover, and the loggerhead sea turtle.

It’s always exciting to see the different people, projects, and passions—especially those in wildlife and environmental conservation—that are all united through the shared use of such powerful and dynamic tools. Having technology partners like Google willing to pull together all of these innovative minds and host Geo for Good is really special and being a part of events like this as members of CCI is exciting. They empower us and those around us to enhance our applications of science and technology to impact policy and protect imperiled wildlife, that way we can hopefully be a part of preventing other threatened and endangered species from meeting the same fate as our T. rex friend.