A man pulls into his driveway after a long day away, fishing and hiking with friends across state lines. His family and neighbors are in the backyard, working on the grill for their last summer cookout. He hands over some wood for the fire that he picked up on his way home, setting the excess down next to some trees in his yard.

What this man doesn’t realize is there are invasive mussels on the bottom of his boat, invasive bug eggs on his car, invasive seeds on his shoes and the wood is infested with invasive bugs. All of which will likely spread to otherwise non-invaded areas.

Zebra mussels. Lantern flies. Cheatgrass. Emerald ash borers. Nutria. Burmese python.

We are all in trouble here.

What are invasive species?

Invasive species are non-native animals or plants introduced to an ecosystem due to human-related activities that can cause ecological damage and compete with native species for resources. Not all non-native species are invasive, but all invasive species are non-native.

Take the lionfish for example. This slow-moving and venomous fish is native to the Indo-Pacific Ocean and the Red Sea. A few fish were released into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Florida in the 1990s. Today, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates there are over a thousand lionfish per acre in some areas. The population likely grew so rapidly to a combination of their high reproduction rates — a single female can produce up to 2 million eggs — and lack of predators.

Lionfish also have become a problematic top predator in the Atlantic Ocean. They will eat several fish per hour and consume a wide variety of fish and crustaceans, out-competing and decimating native fish populations.

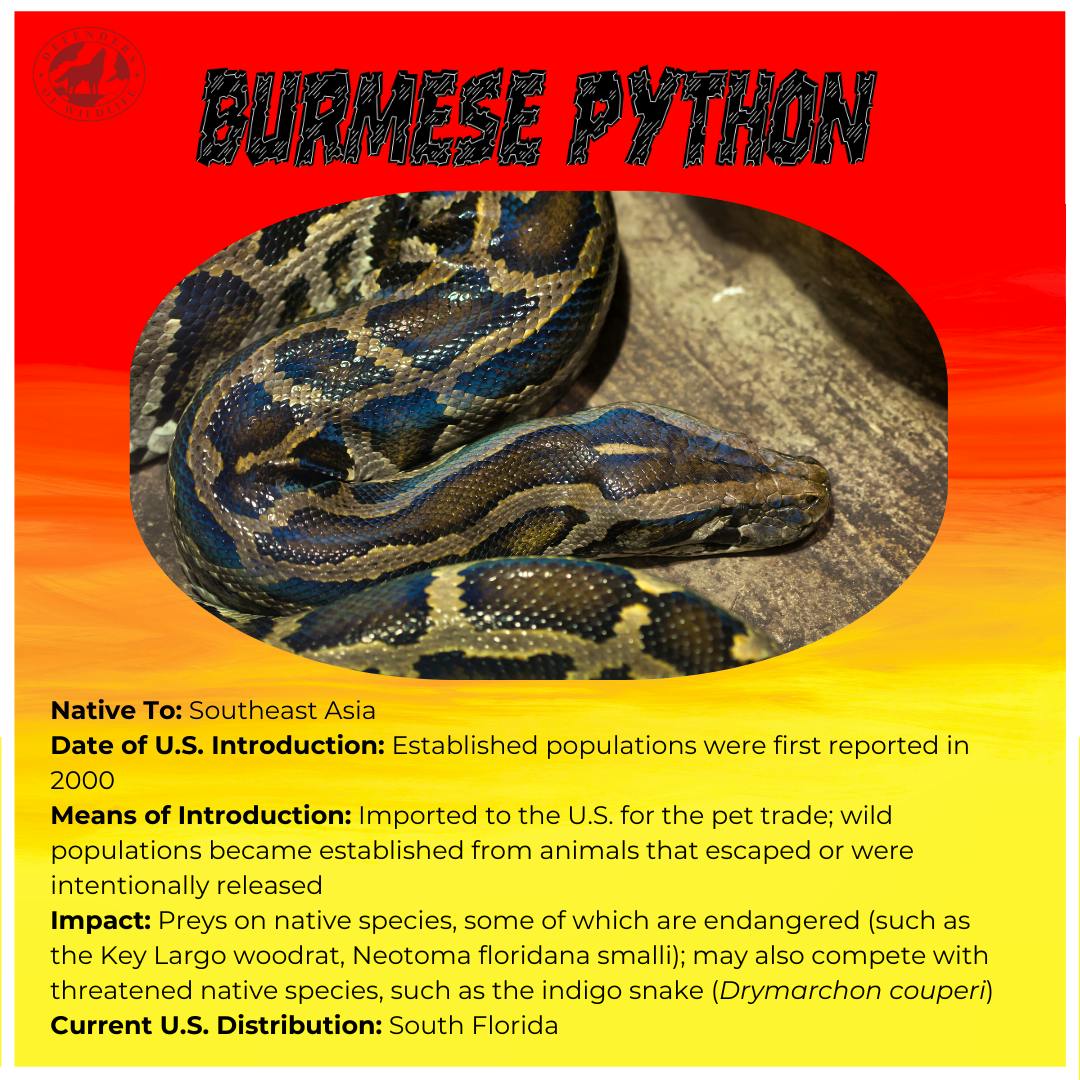

Intentionally releasing non-native animals, however, is just one way invasive species are introduced. It’s suspected the invasive Burmese python was introduced in Florida through the pet trade. Nutria, a type of large rodent from South America, were imported so fur trappers could profit from their coats.

Another common way invasive species are introduced is unintentionally through imports. Spotted lanternflies were suspected to have stowed away in stone imports from Asia. Emerald ash borers likely rode in on infected ash wood and zebra mussels likely entered the United States through commercial cargo ship’s ballast water discharge.

Why are these animals scary?

More than 6,500 invasive species have been identified in the U.S. In their native habitat, these animals are not scary at all. But where they have no natural predators to control their booming populations, they are terrifying.

Invasive species are one of the leading drivers of the biodiversity crisis, disrupting the important interactions that contribute to healthy native ecosystems through predation, competing for resources like food and water, and transmitting diseases. Additionally, they are a major factor in roughly 40% of endangered species listings.

Gunnison sage grouse, for example, are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The less than 4,000 birds left in the wild rely on sagebrush habitat for food, cover and mating grounds. Cheatgrass, an invasive species, provides none of this and is invading and outcompeting the native sagebrush plants across the Great Plains, posing a direct threat to the Gunnison sage grouse.

So, are invasive species dangerous to humans?

The animals and plants themselves are generally not dangerous to humans. The impact each species has on our food and environment poses a greater threat.

Invasive Burmese pythons can pose threats to people. These snakes can grow up to 16 feet long and kill their prey by coiling around and suffocating it. Humans, however, are not generally on the menu. If one does slither across your path, the best way to stay safe is to keep your distance.

The venomous fin rays and spines on lionfish are not fatal to humans but can cause serious injury. Beach goers should keep their distance and avoid stepping on or touching lionfish. If you were to catch one while fishing for other species, be careful not to touch their spines and kill it immediately.

Help de-invade our environment!

"Invasion of the Body Snatchers” instills fear of sci-fi aliens and the other scary movies we’ve looked at falsely portray our native wildlife. It’s up to all of us to rewrite the narrative to say invasive species are the real scary beings in our environments. Here are five ways to help protect against invasives:

- Be a responsible pet and plant owner. Only purchase pets you can verify were collected and imported using sustainable and humane practices. If you decide you can no longer care for a pet, do not release it into the wild. Instead, take it to a shelter or find someone who can care for it instead. For plants, check which species are considered invasive in your area and remove them from your garden.

- Clean your shoes and gear before entering a new place. Hitchhiking seeds or invertebrates can easily travel long distances on people, pets, firewood and outdoor equipment to invade a new area. Check and follow all safety rules when hiking or boating to prevent these accidental introductions.

- Identify or kill on site. Depending on the invasive species and local laws, the best course of action upon encountering one is to report it or kill it. Also check out organized invasive plant removal events in your community.

- Support policies that can help prevent new invasives from entering the U.S. Advocate and vote for policies requiring screening and inspection before plants and animals come into the country. Additionally, stronger wildlife trade treaties and laws can help stop the spread of invasives.

- Spread the word about invasive species in your state. Share with your friends, family and followers how terrible invasive species are for our ecosystems and what your state requests you do when you properly identify one.