ESA protection proposed

Tipping the scale at a mere 25 to 40 pounds, a solitary wolverine can still cause a grizzly bear to turn tail in a battle over food. What this feisty predator can’t face down on its own is climate change. But the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (FWS) recent proposal to protect the wolverine in the lower 48 states may now give the species a fighting chance.

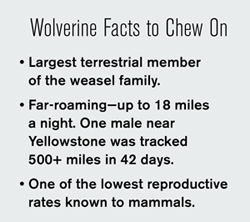

Once found throughout the Sierra Nevada, North Cascades and northern and southern Rocky mountains, and sometimes in the Great Lake states, wolverines almost disappeared by the early 1900s after unregulated hunting, poisoning and trapping campaigns. Trappers prized the luxurious fur of these members of the weasel family—along with otters, minks and martens—for parka hood trim in particular.

Scientists estimate only about 250 to 300 of these bear-cub-sized hunter-scavengers now roam the lower 48 states, primarily in increasingly isolated mountain strongholds in Idaho, Montana (which still allows trapping), Oregon, Washington and Wyoming. A couple of lone dispersers recently arrived in California and Colorado as well.

Such low numbers have long concerned Defenders, which took multiple legal actions after nearly a decade of pressing FWS to act. In 2010, the agency decided the wolverine did qualify for Endangered Species Act protection, but needed to prioritize other more endangered species for listing. The recent proposal to list comes after a court-ordered deadline.

If finalized, federal protections would stop the trapping of wolverines in Montana and require FWS to create a recovery plan with specific steps to restore the species. It would also provide additional resources for research and population monitoring. Included in the proposal are provisions to establish an experimental population in the southern Rockies that will help pave the way for possible wolverine reintroductions.

If finalized, federal protections would stop the trapping of wolverines in Montana and require FWS to create a recovery plan with specific steps to restore the species. It would also provide additional resources for research and population monitoring. Included in the proposal are provisions to establish an experimental population in the southern Rockies that will help pave the way for possible wolverine reintroductions.

“With climate change reducing their available habitat, wolverines are becoming increasingly isolated from each other,” says Kylie Paul, Defenders’ Rockies and Plains representative. “Federal protection will help wolverines survive a warming world by removing threats such as trapping in Montana and offering options for reintroductions, giving them a better chance to move safely across their scattered habitats.”

Female wolverines don’t reproduce every year and when they do, they require deep snow into late spring to raise their young. They dig dens up to 20-feet deep in snow-covered boulder fields and avalanche wreckage. But studies show that climate change could cause wolverines to lose two-thirds of their snow-covered habitat in the Lower 48 by the end of this century.

“If they are to have a shot at survival in the long term, we need to bolster their numbers now before their habitat dwindles even further,” says Paul.

Only select articles from Defenders are available online. To receive 4 issues annually of the full award-winning magazine, become a member of Defenders of Wildlife!