Americans love their road trips, especially across the West to tour the national parks and quintessential mountain landscapes of the Rockies and the Cascades. We drive hundreds of miles across broad shrubby expanses in search of jagged peaks, often overlooking the enchantments spread out right before us. These in-between lands — known as the Sagebrush Sea — are a collage of shrubs, grasses and forbs and teem with iconic wildlife some of whom live nowhere else and depend entirely on this habitat for survival.

While the greater sage-grouse, with its spectacular mating dance, is perhaps the most well-known, hundreds of wildlife species — including nearly 200 migratory and western birds, migrating mule deer and pronghorn — reside within the Sagebrush Sea. Powerful raptors like the golden eagle soar over the vast expanses while other carnivores, like weasels, badgers, cougars and wolves, prowl through the vegetation — all trying to survive in this complex, intricate and fragile place.

The sagebrush, of which there are many varieties, anchors this landscape. Sagebrush are like parents of the sagebrush sea, providing home, refuge and sustenance to other plants and wildlife. A combination of deep taproot and shallow diffuse root system enables the sagebrush to extract moisture and nutrients from deep in the soil column and then make them available to nearby grasses and forbs sheltering under the sagebrush’s protective canopy. Its protein-rich leaves sustain wildlife through the harsh winter months when smaller plants are buried deep in snow.

Since the arrival of Euro-Americans and the advent of the cow and plow, the Sagebrush Sea has been extensively grazed, converted to agriculture and developed. Millions of hectares have been altered or eliminated and now less than 10% remains intact. For decades, government agencies purposely removed sagebrush from vast acreages for reseeding with non-native grasses, primarily to benefit livestock grazing. In more recent decades, oil, gas, coal and wind development have surged, leaving the once continuous expanse fragmented, pockmarked and scarred.

Exotic (i.e., non-native) grasses and weeds continue to expand across the sagebrush sea displacing native perennial grasses and forbs and disrupting natural fire cycles. Greening up and drying out earlier than native perennial grasses, exotic grasses provide contiguous swaths of dried fine fuels that facilitate fire spread and ignitions. Following fire, they can often re-establish more effectively than native grasses further contributing to wildfires. Cheatgrass is one of the worst villains: on over ten million acres, it now blankets what used to be vibrant native habitat.

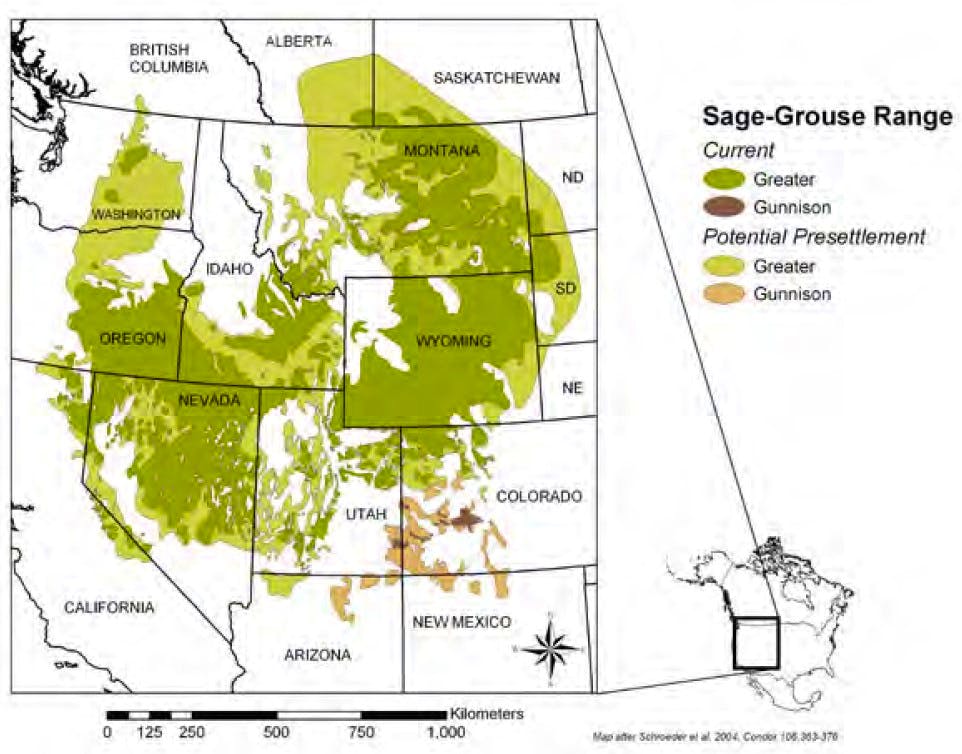

Some worry that this biome is teetering on the edge. Displaced and stressed, native wildlife are struggling. Take for instance the greater sage-grouse. As many as 16 million greater sage-grouse once inhabited 297 million acres of sagebrush grasslands across the West. Today, sage-grouse range is half of what it once was, and populations have declined to less than 10% of historical numbers. Over the last four years (2015-2019), state-level data suggest sage-grouse populations have declined 44% on average.

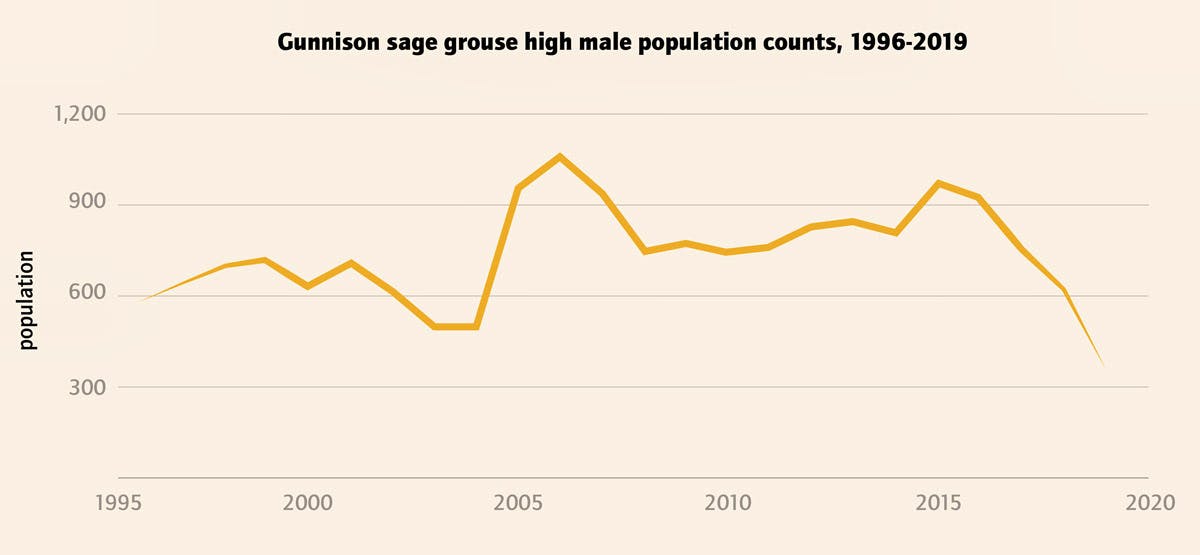

Similarly, the Gunnison sage-grouse, a cousin of the greater sage- grouse, is also in trouble. Once a denizen of the entire Southern Rockies, the Gunnison sage-grouse has lost over 90% of its former range and now is constrained to dwindling pockets of habitat in southern Colorado and Utah. Recent population monitoring revealed the lowest three-year running average ever. The entire species now numbers under 2,000 birds based on the 2020 counts.

Further, over half of the sagebrush obligate birds are in decline, including the sage thrasher, sage sparrow and Brewer’s sparrow. Biologists are worried about small mammals as well. While there is a paucity of information available about small mammals, a concerted effort to trap them in the early 2000’s revealed that they are absent from much of the habitat deemed suitable.

Despite this, we continue to develop and degrade this already embattled ecoregion. In the last four years, the federal government leased over 3 million acres of designated greater sage-grouse habitat for oil and gas development. Grazing continues as well on just under 100 million acres within the larger sagebrush biome even though about one-third of the grazed acres are in substandard condition. By our modest estimates, more than 30% of the sagebrush biome in federal control has been affected in the last decade by oil and gas leasing, deleterious grazing, wildfires and utility/road rights of ways.

In 2020, in response to a Trump administration effort to reduce protections to the Sagebrush Sea and its wild inhabitants, a number of prominent scientists wrote a letter to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). They warned that the administration’s current approach to the Sagebrush Sea “suggest[s] that the BLM has no viable landscape-scale approach to managing impacts to sage-grouse or its habitats” and “will likely lead to continued degradation and loss of sage-grouse habitats as development in these habitats proceeds.”

Seventeen years ago, several research scientists published an article titled “Teetering on the Edge or Too Late?” in which they bluntly stated, “Our primary challenge….may be to convince our society of the intrinsic value of sagebrush ecosystems and their unique biodiversity. This change in mindset will have to be followed by a firm commitment by federal and state agencies to provide the resources necessary to resolve issues presented in this paper. Only with this concerted effort and commitment can we afford to be optimistic about the future of sagebrush ecosystems and their avifauna.”

The authors made a series of recommendations that are as relevant today as they were 17 years ago.

First, better understand the effects of land practices on native ecosystems by designing experiments with “strong statistical designs that include treatments and controls” He urged agencies to integrate their many planned treatment projects into an experimental framework so we can learn what works, what does not and why.

Second, protect at least 10.6 million acres (about 10%) in a nature reserve would ensure that the most intact remaining habitats are not committed to destructive land uses and activities. Because 10.6 million acres of contiguous intact habitat no longer exists, we need to protect the best remaining blocks, and then enlarge and increase connectivity among them applying scientifically- sound restoration approaches.

(In 2012, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity called for the protection of at least 17% of the world’s terrestrial systems by 2020. In 2019, it updated this call to action asserting that the world must protect 30% of its terrestrial ecosystems by 2030 to stave off further mass extinction. Less than 3% of the sagebrush sea is protected today.)

Third, establish a federal policy to require use of ecologically appropriate native plant species in all shrub-steppe restoration projects, one simple yet dramatic step to “redirect[] the ecological trajectory of these landscapes way from ecological dysfunction and toward ecological resiliency.”

Despite these recommendations from 17 years ago, we are still witnessing the loss of sagebrush habitat and wildlife battling against extirpation and extinction. We have yet to safeguard and reconnect remaining intact habitat blocks. We have yet to insist that federal agencies stop planting non-native species as a matter of course. We have yet to permanently protect 30% of the Sagebrush Sea.