As the planet warms, protecting rivers in the arid Southwest becomes even more crucial

by Peter Bronski

© rayMond gehMan

I'm flanked by a line of Fremont cottonwood trees overlooking the gently flowing waters of the Gila River from what was once an earthen levy in southwestern New Mexico's Cliff-Gila Valley. Arriving last night during the tail end of the monsoon season in September, I hunkered down to ride out a thunderstorm that blew over the river's headwaters in the Mogollon Mountains near the 1,400-acre Gila Riparian Preserve.

As New Mexico's last major free-flowing river, the Gila is an anomaly in an arid region where the historical tendency is to "control," dam, divert and allocate every last bit of water. This is what makes the Gila vitally important in the Southwest. As a thriving ecosystem, it can offset the negative environmental impacts of water development projects on other rivers, and it is also an example of what a healthy river should look like.

In short, "It's the last river standing in the state," says Mike Fugagli, a local ornithologist and former naturalist for The Nature Conservancy in nearby Silver City. And with climate change hitting the water supply and the wildlife of the Southwest hard, the future of the Gila may be more important—and threatened—than ever.

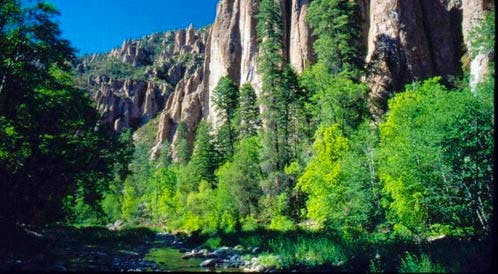

The upper Gila sits at a convergence of ecological regions, where the montane forests of the southernmost Rocky Mountains collide with the Chihuahuan Desert extending up from Mexico, and the Sky Islands reaching into southwestern New Mexico from Arizona. The Gila weaves its way through tight canyons (called boxes) and broad valleys with expansive floodplains. From its uppermost box, where it slices through the Mogollon Mountains, the Gila spills out into the Cliff-Gila Valley, the river's first broad floodplain. When it eventually crosses into Arizona, the river rapidly degrades, tamed and contained behind the Coolidge Dam, then literally sucked dry by the city of Phoenix. Technically, the Gila is a tributary of the Colorado River, but it no longer reaches there. Its water disappears into the desert sands just outside Arizona's most populous city.

The bulk of the water comes primarily in two major bursts, like a two-blip annual heartbeat rhythm, Fugagli explains. The monsoon storms, which typically last from July through August, supply up to 50 percent of the watershed's annual surface water. The winter snowpack from the Mogollon Mountains provides the balance when it melts during spring. "When you look at other southwestern rivers like the Rio Grande, they're a flat line," Fugagli says, referring to their dam-controlled flow rates. "Those rivers are dead."

Fugagli raises a pair of binoculars and focuses on a mature cottonwood in the distance. He's looking for the imperiled western yellow-billed cuckoo, which winters in South America. For each of the last five years one particular pair has returned to nest not only on this river, or in this valley, but in this particular tree. It's a testament to the present-day health of the Gila. Nearly all but extirpated from the western United States, the cuckoo is now utterly reliant on the Gila.

The common black hawk, listed as threatened in New Mexico, is another iconic bird of the Gila. In fact, the largest U.S. population is found here. Of the 225 nesting pairs in the United States, 28 live in the riverside cottonwood forests, called bosques, of the Cliff-Gila Valley alone, amounting to one nest every half-mile along the valley's 14-mile stretch of river. "Birds that are scarce elsewhere in the Southwest are abundant here," Fugagli says. In fact, more than 350 of North America's 900-plus bird species can be found on the Gila. Though the healthy, mature cottonwood corridors like those found along the Gila represent just one half of 1 percent of New Mexico's land area, they account for some 80 percent of its avian diversity. This presents both an opportunity and a challenge for conservation.

But birds aren't the only creatures that thrive here. The river boasts one of the most intact populations of native fish in the Southwest, including the federally threatened Gila trout. Healthy populations of black bears also abound along with mountain lions, coatis (related to raccoons), ringtails, javelinas (related to wild boars) and remnant populations of muskrat, beaver and otter. The latter three were all trapped to the brink of extirpation elsewhere in the Southwest. Also here are rebounding populations of reintroduced species that were missing decades earlier: elk, bighorn sheep and the Mexican wolf, whose recovery has been one of Defenders of Wildlife's main focuses.

All of this—the natural river hydrology, the mature bosques, the healthy wildlife populations—leads Allyson Siwik, executive director of the Gila Conservation Coalition, to characterize the Gila ecosystem as "relatively pristine," although this may not hold true for long.

The Gila sits at another convergence, one of competing potential uses for its water: flood-irrigated agriculture and pasture, municipal water supplies, mining, potential water development projects, and lastly, conservation. Of those, conservation has proven the hardest sell. Keeping the Gila healthy means leaving water in the river, but under the West's water rights law of "use it or lose it," giving the Gila back its water constitutes losing those rights. "In such a dry region, water was seen as too valuable to leave in the river," says Kara Gillon, Defenders of Wildlife's water expert. "Fortunately, we're starting to see our water policies reflect the value of leaving water in our streams."

The Gila has survived its share of significant threats before. In its distant past, the Mimbres branch of the Mogollon culture lived along the upper Gila during the turn of the first millennium. Like today's residents, they employed flood-irrigated agriculture, mostly to grow corn. In a way, they subjugated the river, took it for granted, crept closer and closer to its banks and became overly dependent upon it. And then, as rivers with natural hydrologies will do, the Gila shifted. It didn't rear up in flood as it did in 2005. Instead, a prolonged drought decimated the Mimbres, and those who survived left the region entirely.

In more recent times, the Gila has somehow survived the convoluted, Byzantine workings of water allocation and law in the West, including the Arizona Water Settlements Act of 2004, which has opened up a new debate about tapping the Gila's waters. The river came closest to "dying" with the proposed Hooker Dam and Reservoir, first authorized by Congress in 1968 and then revisited in the 1980s. The dam, had it been built, would have sat at the upper end of the Cliff-Gila Valley and would have inundated miles of what is the present-day Gila Wilderness.

But of the Gila's current and previous threats, one trumps them all: global warming. Southwestern New Mexico is already seeing signs of climate change. Low elevation landscapes have increased rates of desertification. Species normally restricted to Mexico and southern New Mexico, such as the coati and the javelina, are extending their ranges northward. And the hydrology of streams is shifting. The Gila's watershed is one defined by a select few perennial streams, which flow year-round, intermittent streams, which flow for only part of the year, and ephemeral streams, which flow only during and immediately after a major rainfall. Now, "perennial streams tend to become intermittent," Fugagli says. "And intermittent streams are becoming ephemeral."

According to a New Mexico Climate Change Advisory Group report, conditions are expected to get worse. Even conservative predictions call for increased variability in the monsoon season, decreased snowpack in the mountains, greater instances of prolonged drought, increased temperatures and a host of other effects that "could kill the perennial nature of the river," says Cooper. It's a sobering potential future for the Gila.

There is some potential for good news though. "The Gila suffers from fewer non-climate stressors and may be better equipped to adapt to climate change," says Gillon. "It has not been fragmented by dams, overrun with invasive species or dewatered from overuse. This means we can use the Gila as a guide for helping other southwestern rivers adapt, because rivers tamed by dams and diversions will suffer more severe consequences from climate change."

Before saying our good-byes, Fugagli gives me one more bit of advice: "The best way to experience the Gila is simply to get in it." Following his recommendation, I head up into the Mogollon Mountains and Gila National Forest and into the Gila Wilderness. These are the headwaters, where the river's west, middle and east forks converge, and where the mountains and valleys gather the snows and rains of winter and the monsoon's flash downpours. This is the birthplace of Geronimo, famed chief of the Apache. And it's a landscape that inspired famed conservationist and author Aldo Leopold, who succeeded in having the Gila proclaimed the nation's first federal wilderness area in 1924.

I begin my trek on the west fork of the Gila River, exploring the preserved cliff dwellings of the Mogollon people, set in a cool shaded canyon with lush vegetation. Climbing up, I am immediately reminded that here water is life. The river is behind me now. I am hiking through the desert. After several miles in the hot, scorching sun, I drop into a canyon, where spring-fed streams trickle to the Gila's robust Middle Fork. Here is another oasis teeming with wildlife. By the time I return to my car, I've covered nearly 17 miles on foot and completed nearly 60 river crossings.

Amazingly, it's not my romp through the wilderness that leaves the most lasting impression. Rather, it's a hike I took with Fugagli and Cooper the day before to Mogollon Box, an overlook offering the most inspiring view of the river—and a vision of hope for its future. "This is my favorite spot on the river," Fugagli says. Here, in one sweeping panorama, I see the river's past, present and possible future. Fugagli reaches down and plucks something up from the dirt—a tiny piece of shiny, black obsidian. "From the Mogollon," he explains, pointing to a flat bench below us alongside the river where they once had a settlement. Next, he points to a floodplain that once was home to agriculture and ranching. Finally, he frames a canyon between his outstretched hands. "That's the Hooker Dam site," he says.

But best of all, if not for Fugagli's encyclopedic knowledge, I never would have known any of it, for the river looks entirely…natural. "It's a demonstration of its incredible regenerative power," he says. Twenty short years ago, the mature cottonwood bosques I look down upon were absent. In their place, the riverbanks were nothing but cobbles. Now, trees and lush riverside vegetation dominate the floodplain, and with the return of the plants, wildlife has repopulated the area as well.

"This is the reason I chose to live here and raise my child here," Fugagli says. "All across the country, it always seemed that ecosystems were degrading. But here, it's getting better every day."

Peter Bronski (peterbronski.com) is an award-winning writer from Colorado who frequently covers environmental topics. His work has appeared in more than 60 magazines.