The world smallest and most endangered porpoise is literally on its last fins. According to the latest population estimate by the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) there are fewer than 30 vaquitas left in the Upper Gulf of California, the only place on Earth where they are found.

In 2014, CIRVA estimated that less than 100 vaquitas were left and an all-out effort to save them was started by the Mexican government. In 2015, Mexico decreed a two-year ban on fishing activities throughout the vaquita’s range, and launched a compensation plan for the loss of income to fishermen, estimated at around $50 million dollars each year. The country also increased law enforcement efforts by inspectors from the Environmental Enforcement Agency, Fishery authorities and the Navy using a new fleet of fast patrol boats, and drones for surveillance of the whole Upper Gulf.

However, it didn’t work, and CIRVA’s estimate of 2016 put the vaquita’s numbers at less than 60. Why? The enormous interest in illegal fishing for totoaba bladders for the Chinese markets. Totoaba is an endemic fish native to the Upper Gulf of California — the same waters as the Vaquita. The fish’s bladders are sold in China for over $10,000 dollars a kilo, which means that a fisherman can make more in just a few weeks of illegal fishing than they would fishing legally for the entire year.

So, fishermen couldn’t care less for the compensation plan or the law and kept on going out to illegally fish for totoaba using deadly gill nets. Although Mexico increased patrols and even had the help of vessels from the organization Sea Shepherd, dead vaquitas kept on appearing on the shores.

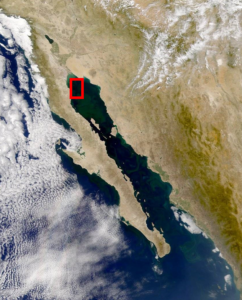

Vaquita are found only in the uppermost Gulf of California, Mexico (© NOAA Fisheries)

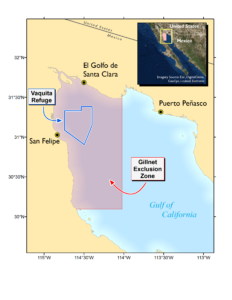

Gillnet exclusion zone designated in the upper Gulf of California (© NOAA Fisheries)

In 2017, Mexico tried a plan proposed by experts, which has helped many other critically endangered species in the past, to capture vaquitas and put them in a safe pen near the coast. The idea was to help vaquitas reproduce safely while trying to get the illegal totoaba fishing under control. But alas, the plan didn’t work either; only two vaquitas were caught, a juvenile which had to be let go and an older female which died from heart failure. CIRVA requested the capture plan be scratched given the risk to have more deaths on a dwindling population.

Fortunately, the acoustic monitoring used to locate the vaquitas for capture produced a bonus result in that experts now know where the vaquita’s last stronghold is situated, an area where the last vaquitas are congregating.

With this information, Defenders of Wildlife, along with Greenpeace Mexico and the Mexican NGO Teyeliz, presented a proposal to the Environment Ministry to protect this area, prohibit fishing, restrict navigation, and increase patrolling. The Environment Ministry accepted the proposal and early in February announced the new measures to protect the vaquita.

This could very well be the last chance for the vaquita to be saved and we are all hoping it will do the trick.