Roads present challenges to the protection of species, their natural habitats, and their unimpeded movement across landscapes, which is why Defenders of Wildlife is very active in reducing the impact that roads have on wildlife survival. Our nation’s transportation network, which you likely take advantage of every day, cuts through natural landscapes and is very much a part of the story of our coexistence with our wildlife neighbors.

In fact, around this time of year you’re bound to see extra reminders that wildlife and roads don’t mix. We have to remain cautious while driving because wildlife are particularly active now: some are preparing to migrate to warmer locales and others, like deer and moose, are entering breeding season. On average, October sees the most wildlife-vehicle collisions, with over 13% of the entire year’s human fatalities due to accidents occurring during this month. In the Center for Conservation Innovation at Defenders, we sift through data like this to better understand and inform wildlife conservation.

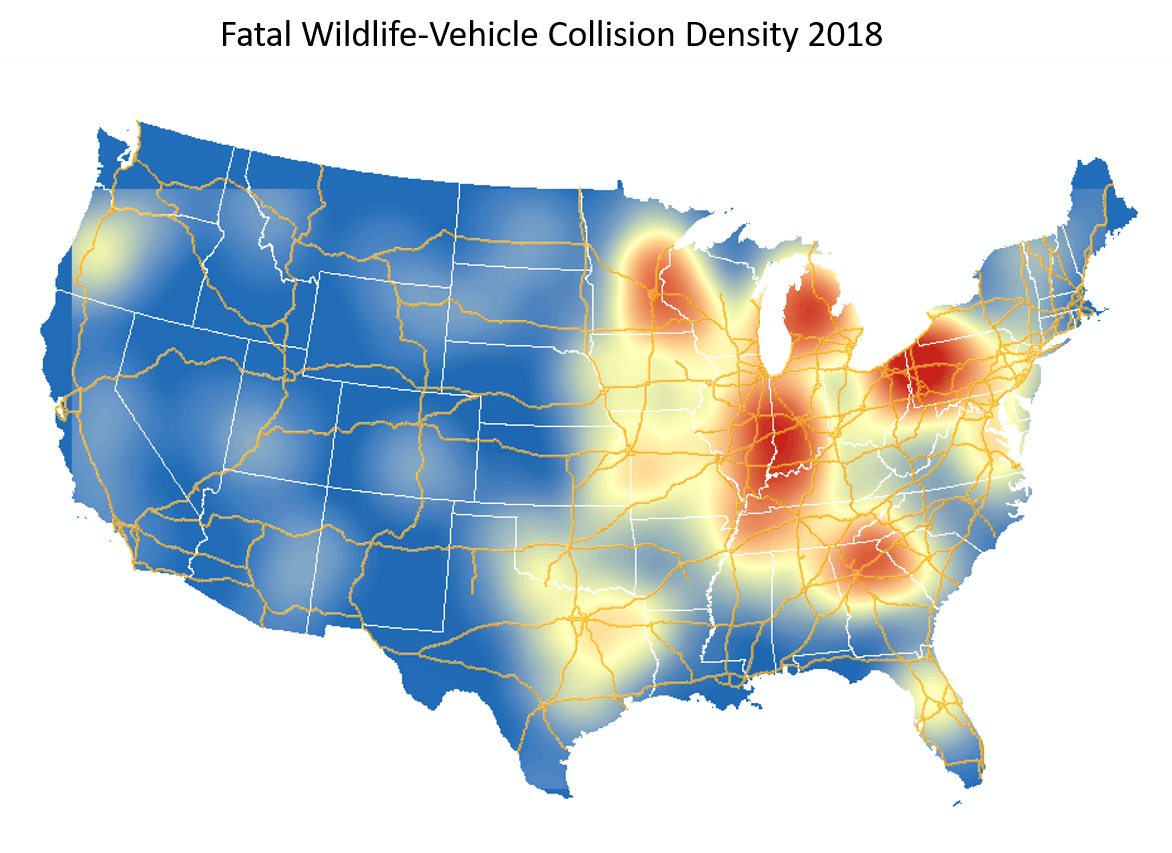

The graphs in this post are based on data from the U.S. Department of Transportation's Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) established in 1975. However, this data is only based on human fatalities. In general, wildlife-vehicle collisions are severely under-reported. Estimates suggest that between one and two million vertebrates are killed every year on U.S. roads – that’s one every 26 seconds! And this number continues to rise by another 7,000 crashes each year.

Roads are the reason why cars end up in the middle of wildlife habitat, so it’s no surprise that there are more reported collisions in states where there are more roads. By far, the highest number of human fatalities reported from wildlife-vehicle collisions and the highest density of roads are in Texas. The lowest is in Hawaii. There are over 4 million miles of public road in the contiguous U.S. As this number continues to rise, so does the number of fatal collisions.

Species at Risk

Vehicle collisions present an immediate danger to human and animal safety. According to a review of fatal animal crashes in nine states, 77% of the struck animals were deer, and a variety of other animals were involved including cattle, horses, dogs, bears, cats, and opossums. For other, less common, wildlife, vehicle collisions are often a key reason why they have become less common: there are at least 21 federally listed threatened or endangered animals species in the United States for which road mortality is among the major threats to the survival of the species. These include:

- Florida panther

- Canada lynx

- Lower Keys marsh rabbit

- ocelot

- Bighorn sheep

- Red Wolf

- San Joaquin kit fox

- American crocodile

- Desert tortoise

- gopher tortoise

- Alabama red-bellied turtle

- bog turtle

- Copperbelly water snake

- eastern indigo snake

- California tiger salamander

- flatwoods salamander

- Houston toad

- Hawaiian goose

- Audubon’s crested caracara

- Florida scrub jay

The Trouble with Roads

Roads cutting through wildlife habitat pose additional threats to species and ecosystems. For one, roads provide greater access to parts of an ecosystem that were previously more remote and intact. These are important habitat characteristics for some species.

Harm: approximately 200 humans and one-two million animals are killed each year in vehicle collisions.

Impede: roads are a major barrier to movement for species like the California tiger salamander that need to travel to ponds to breed.

Fragment: when roads and human development cut through habitat, they can separate species into smaller populations that reduce gene flow and increase the risk of localized extinction. This is one of the major threats to the North American wolverine.

Distress: roads also bring with them noise pollution. Many bird species like dusky flycatcher are sensitive to noise pollution and end up leaving their homes behind. Others like quail can experience hearing loss.

Introduce: roads not only transport humans, but also invasive plants and animals that can alter an ecosystem or outcompete native species.

Pollute: even aquatic species like the frogs and salamanders can't hide from the impact of roads. Rain and flood waters take with them extra sediment and pollutants left on the roads they flow across on their way to lakes, streams, and oceans.

How You Can Help

So what can be done to help protect our wildlife from devastating encounters with roads?

Protect the Roadless Rules: In 2001, the U.S. Forest Service adopted a nationwide rule to protect large tracts of relatively undisturbed public forestland from road construction and destructive timber harvest. Setting aside U.S. forest in these roadless areas was groundbreaking, yet they only represent seven percent of total forest area in the lower 48 states. Defenders recognizes the importance of protecting roadless areas as wildlife refuges from destructive human activities. Our Federal Lands team, with support from the Center for Conservation Innovation and other departments throughout Defenders, is actively fighting petitions to weaken these protections in both the Tongass National Forest in Alaska and the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest in Utah.

Support Wildlife Crossings: Defenders has been working with the Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management to encourage the installation of wildlife friendly fencing and crossings along roadways. Under- and overpasses help guide animals across roads without putting them in direct contact with vehicles. Research shows that wildlife crossings save money and lives, both human and animal. Defenders has been involved in facilitating the installation of wildlife crossings and slower speed zones to protect species like the Florida panther and Pacific fisher. In working with the Department of Transportation, we advocate for conservation-minded transportation planning that considers the dangers that motor vehicle traffic and habitat fragmentation present for panthers and other wildlife. The largest crossing in the world is planned to stretch 200 feet above ten lanes of busy highway outside of Los Angeles, California. Wildlife crossings can be creatively designed to fit the specific species trying to cross. Check out this diversity!

Avoid Using Road Salt: Salt can be a natural resource of much needed minerals for wildlife. However, by attracting some species to roadsides, road salt can put animals in danger from passing cars. Road salt can also increase the amount of minerals in soil and waterways to levels dangerous for some plant, insect, and aquatic species.

Volunteer as a Wildlife Crossing Guard: Many local conservation groups host events in the early spring where volunteers serve as crossing guards for amphibians migrating to vernal pools. It’s also a great opportunity to learn more about your wildlife neighbors! Keep an eye out in spring for programs and events near you! Defenders awarded funds for the construction of this amphibian crossing tunnel in Monkton, VT that was completed just last year.

Message Your Senator: Defenders was instrumental in the passage of the New Mexico Wildlife Corridors Act. In May 2019, a similar act - the Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act - was introduced to the U.S. Senate. It would give key agencies authority to designation National Wildlife Corridors on federal lands in order to create a corridor network for safer movement of wildlife.

Continue to Support Defenders' Conservation Initiatives

And of course, stay tuned for more to come from the Center for Conservation Innovation!