Defenders calls on FWS to do right by jaguars

Once in a blue moon, an endangered jaguar gets a foothold on the species’ old stomping grounds in the American Southwest. But to get there, a jaguar must move through a gauntlet of guns, vehicles, towns and barricades at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Once in a blue moon, an endangered jaguar gets a foothold on the species’ old stomping grounds in the American Southwest. But to get there, a jaguar must move through a gauntlet of guns, vehicles, towns and barricades at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Biologists have confirmed only seven in southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico over two decades—including media sensations Macho B—who died in 2009 and had been photographed around the Arizona-Mexico border since 1996—and El Jefe who was last captured on a trail camera a few years ago. These sightings are rare but fill conservationists with hope that the cat can make a comeback north of the border.

Once roaming as far north as the Grand Canyon, jaguars were common in Texas and may even have claimed territory in California and Louisiana. But by the early 20th century, they had largely disappeared, killed off by government predator-control agents, livestock producers and hunters.

Today jaguars—protected under the Endangered Species Act—are ripe for a rebound, particularly given that populations of their favorite prey—deer and javelinas—are more abundant than they were 100 years ago, when jaguars still mated and raised young in the United States.

But obstacles remain. They include a lack of commitment from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the agency charged with recovering and protecting the cats, says Rob Peters, Defenders’ senior southwestern representative.

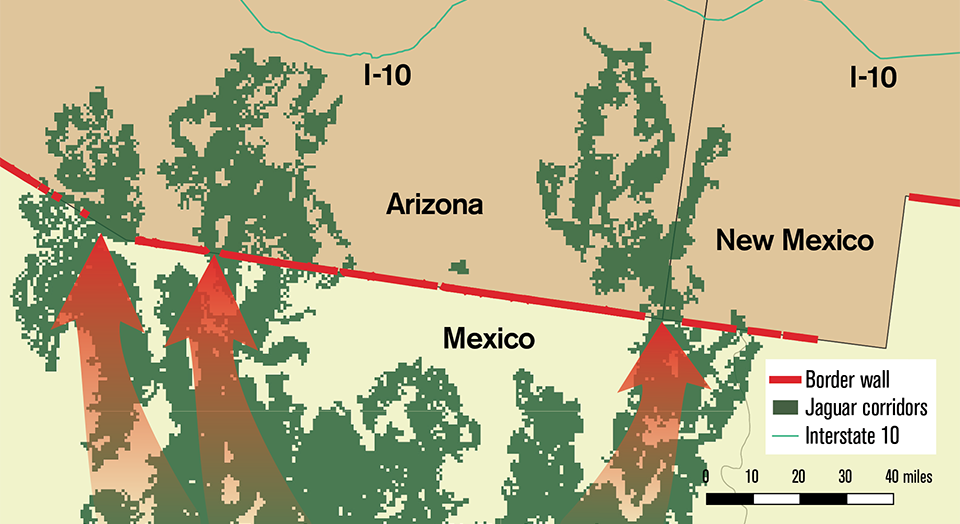

With a species recovery plan underway, Defenders is calling on FWS to enlarge the planned recovery area to include millions of acres north of Interstate 10, to protect important movement pathways across the border and to take a hard look at bringing female jaguars from outside the United States to join the males and have cubs on U.S. soil. Females do not typically disperse long distances. Add cities, highways and other obstacles to the mix, and recolonization by female jaguars is unlikely without assistance.

Jaguar mortality—including deaths caused by guns and vehicles and the indirect mortality associated with mining and other activities that destroy habitat—also must be prevented. “FWS must champion jaguar recovery in the United States, and all the federal and state agencies charged with safeguarding jaguars must make recovery a higher priority when considering projects, like mining, that could harm the cats and their habitats,” says Peters.

Another big obstacle to recovery is a literal one: The proposed border wall. Already, more than 600 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border is blockaded by walls and other barriers in all four southern border states: Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas.

Intended to block people, these barriers also impede animals. In Texas, they keep animals from accessing the Rio Grande River, a vital water source. In Arizona, the border wall and its associated roads, lights, towers and patrols are already degrading three large parcels of protected public lands totaling 3 million acres in Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and Barry M. Goldwater Range.

President Trump’s executive order, signed in January, authorizes extending the artificial barrier farther, blocking jaguars and other endangered wildlife, including Sonoran pronghorn, Mexican gray wolves and ocelots that need to cross the border to find food, water and mates.

“For people pursuing a better life and for borderland wildlife fighting to survive, a border wall will not solve problems, it will only create or exacerbate them,” says Jamie Rappaport Clark, Defenders’ president.

“Only with the unwavering commitment of government agencies and the support of conservation groups, scientists and citizen advocates will el tigre make it back to stay in the USA,” says Peters. “The jaguar is as much a part of our country’s natural heritage as the bald eagle or the grizzly bear. These stealthy survivors have been able to thrive within just miles of Tucson and smaller towns, crossing highways to move from mountain range to mountain range. If they can stay out of harm’s way, conditions are suitable for them to stay in the United States and for other jaguars to follow.”

Cool Fact

The jaguar is the world’s third-largest feline, behind tigers and lions. It is the only big cat in the Western Hemisphere that roars.

Read Defenders’ new report Bringing El Tigre Home at http://www.defenders.org/eltigre.

Only select articles from Defenders are available online. To receive 4 issues annually of the full award-winning magazine, become a member of Defenders of Wildlife!